The idea that people are connected through just «six degrees of separation,» based on Stanley Milgram’s «small world study,» has become part of the intellectual furniture of educated people. New evidence discovered in the Milgram papers in the Yale archives, together with a review of the literature on the «small world problem,» reveals that this widely-accepted idea rests on scanty evidence. Indeed, the empirical evidence suggests that we actually live in a world deeply divided by social barriers such as race and class. An explosion of interest is occurring in the small world problem because mathematicians have developed computer models of how the small world phenomenon could logically work. But mathematical modeling is not a substitute for empirical evidence. At the core of the small world problem are fascinating psychological mysteries.

The «small world» experiments

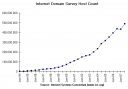

Stanley Milgram was an American researcher in experimental social psychology at Harvard University in Boston, USA. Beginning in 1967, he began a widely-publicized set of experiments to investigate the so-called «small world problem.» This problem was rooted in many of the same observations made decades earlier by Karinthy. That is, Milgram and other researchers of the era were fascinated by the interconnectedness and «social capital» of human networks. While it is unknown how directly Milgram was influenced by Karinthy’s work, the similarities between the two authors are remarkable. However, while Karinthy spoke in abstract and fictional terms, Milgram’s experiments provided evidence supporting the claim of a «small world.» His study results showed that people in the United States seemed to be connected by approximately six friendship links, on average. Although Milgram reportedly never used the term «Six Degrees of Separation,» his findings likely contributed to the term’s widespread credence. Since these studies were widely publicized, Stanley Milgram is also, like Karinthy, often attributed as the origin of the notion of Six Degrees. Here’s the latest Small World Experiment, currently in progress.

Theoretical Basis

It is important to realize that «6 degree of separation» is only in the average sense. For example, there may be a secluded population on an island nation which has had little contact with the outside world — or a secluded population which has had little contact with anyone in living memory, although such a hypothesis is almost completely improbable in the 21st century, it is still conceivable. Thus, under the «knows a living person» graph, the path length between someone in that tribe and outside of it is infinity/undefined.

If you assume the world population is 6 billion people, and everyone has the same number of friends or ‘connections’, and that each person is just as likely to know one person as any other person (save for geographic limitations), then measuring the degree of separation only becomes a simple mathematical formula of determining the exponent that will yield the population if you raise the average number of friends of each person by that exponent. In other words,

(average number of friends per person) ^ (degrees of separation) = total population

Let f = average number of friends Let d = degrees of separation Let p = population

f^d = p d * ln f = ln p d = ln p / ln f

Finding the average number of friends can be determined by random sampling. However, since we already have a good idea what the degree of separation is, let’s determine ‘f’ and consider its reasonableness.

f^d = p f = dth root of p

If we take the 6th root of 6,000,000,000, we get approximately 42.

6th root of 6,000,000,000 = 42.628 ln(6,000,000,000) / ln(42) = 6.024

Knowing 42 people is not unreasonable to a person. One class or workplace can contain 42 people. Thus, if 42 of your friends knows 42 other people, and they each know 42 more people, and so on and so on until 6 chains have been formed, then that will encompass 6 billion people.

In fact, if we take the 5th root of 6 billion, we get about 90, which in today’s connected age is not unreasonable for some people. The 7th root is 24. So if we assume that everyone in the world knows between 24 to 90 people each, then we can prove the degree of separation is between 5 and 7.

The reason this works is because as the number of chains increase, the total percentage of the population ‘known’ increases exponentially. For example, if the population is 16, and each person is restricted to knowing at most 2 people, then the degree of separation is 4. 1 person who knows 2 people is 2. If those 2 people know 2 more people, the total is 4. If those 4 people know 2 people each, the total is 8. If those 8 people know 2 people each, the total is 16.

4th root of 16 = 2 2^4 = 16

If the population is split in two groups of 8, perhaps by geographic boundaries, then it would be impossible to ‘know’ the entire population or have a connection between all individuals.

The advent of affordable intercontinental air travel in the 20th century has reduced these geographic boundaries, such that even if one individual does not know someone on another continent, they are likely to know someone else who has been to another continent. The more the population intermixes and comingles, the more even and regular the degree of separation is between any two random people in that population.

«The representation makes no difference between one-way relationships and those that are based on reciprocity. Someone who has all the luminaries on his blogroll but whose contribution for whatever reason is not very visible will seem just as connected as someone else who is widely read and recognized. How could «directions» of relationships be displayed?»

Tags: Science Simplified, Vida Enigmática by Dr. Leslie Brown

1 Comment »

Â